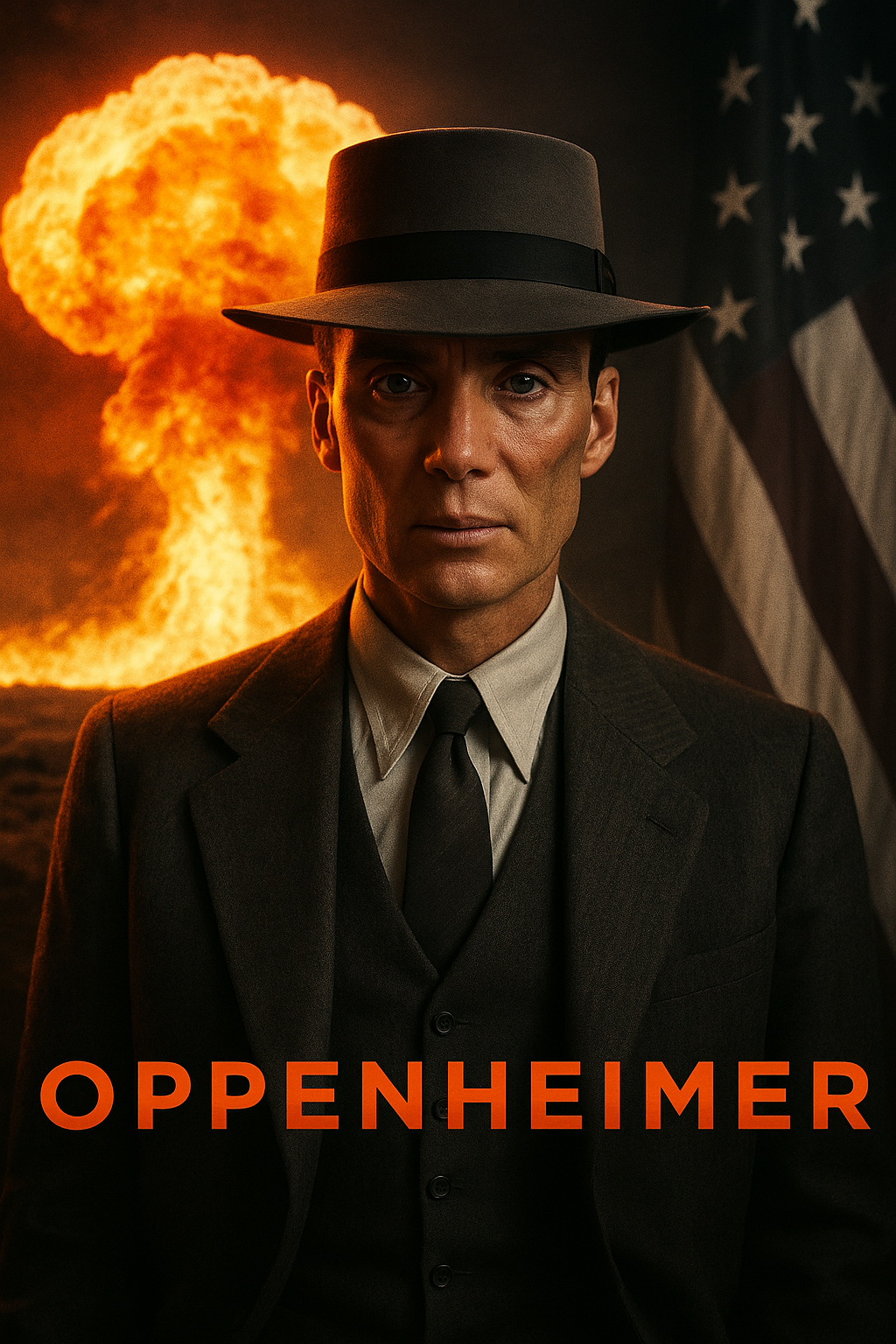

How Nolan uses “fission vs. fusion” storytelling to build his most complex narrative since Memento.

🟥 Introduction: Nolan Didn’t Just Make a Biopic — He Engineered a Narrative Machine

“Oppenheimer” isn’t a biographical drama in the traditional sense.

It is a structural puzzle, built on a scientific metaphor that shapes the entire film:

Fission and Fusion.

Two scientific processes.

Two narrative timelines.

Two conflicting perspectives.

Two versions of the same historical events.

Nolan constructs Oppenheimer’s story not around chronology, but around:

- political memory

- subjective guilt

- objective judgment

- competing narratives

- the weaponization of perspective

This analysis breaks down:

- how the dual-timeline system works

- why one timeline is in color and the other in black-and-white

- how memory vs. record shape the plot

- how Nolan manipulates time to reflect accountability

- how fission/fusion metaphors structure character arcs

- why the film’s nonlinear design is essential to its emotional punch

Let’s dissect the narrative engine behind Oppenheimer.

🟥 1. The Two Timelines: “Fission” vs “Fusion” (Nolan’s Official Terminology)

Nolan identified the timelines with scientific labels:

⭐ 1. FISSION (COLOR) — Oppenheimer’s subjective experience

- Emotional

- Internal

- Memory-driven

- Imperfect, biased, interpretive

- The world as Oppenheimer believes it happened

This is the version fueled by fragmentation — splitting events into emotional charges, like atomic fission itself.

⭐ 2. FUSION (BLACK & WHITE) — Strauss’s objective perspective

- Procedural

- Facts, hearings, depositions

- Documentary-like

- Historical record

- The world as the system sees it

Fusion is about combining elements into a singular, unified judgment — just like nuclear fusion.

This is not simply a color choice.

It is a philosophical framing device.

🟥 2. Why Color vs Black-and-White Matters (The Psychological Effect)

The dual palette isn’t aesthetic — it creates two cognitive modes:

⭐ Color = Subjectivity, Emotion, Memory

Color signifies:

- Oppenheimer’s internal experience

- his guilt

- his anxieties

- his rationalizations

- his constructed memories

The camera becomes his consciousness.

These scenes are filled with:

- shallow depth of field

- fragmented insert shots

- rapid cuts

- surreal visual moments

- hallucination-like imagery

It’s the world as he perceives it.

⭐ Black & White = Objectivity, System, Judgment

Black-and-white scenes represent:

- committees

- hearings

- investigations

- bureaucratic truth

- institutional memory

These are shot more rigidly, more still, more distant.

The world not as Oppenheimer feels it, but as the system records it.

🟥 3. The Narrators: Who Controls Each Timeline?

⭐ FISSION (COLOR)

Narrator: Oppenheimer himself

This timeline is told from:

- his memories,

- his emotional reactions,

- his psychological journey.

It is fundamentally unreliable because memory is not truth — it is interpretation.

⭐ FUSION (B&W)

Narrator: Lewis Strauss

This timeline reflects:

- political battles

- ego-driven narratives

- weaponized testimony

- historical reputation

- bureaucratic power plays

This is not subjective emotion — it is objective documentation (or the illusion of it).

This duality creates a tension:

Whose version of history survives?

🟥 4. The Structural Pattern: Two Story Arcs Moving in Opposite Directions

Nolan designs the film so each timeline moves with opposite momentum.

⭐ Fission Timeline (Oppenheimer) moves FORWARD

It starts with:

- his student years

- quantum theory

- political ideology

- Los Alamos

- Trinity Test

- Hiroshima & Nagasaki aftermath

His story builds toward the loss of control — the bomb leaves his hands.

⭐ Fusion Timeline (Strauss) moves BACKWARD

It begins with:

- Strauss’s political rise

- the Senate confirmation hearings

- testimonies

- character attacks

And as it progresses, it uncovers:

- Strauss’s insecurities

- past betrayals

- personal vendettas

- weaponization of Oppenheimer’s reputation

The timelines eventually collide at a singular point of truth.

This is narrative fusion — multiple perspectives merging into a single revelation.

🟥 5. Nolan’s Time Philosophy: Why Nonlinear Storytelling Is Essential

Oppenheimer is not nonlinear for style.

It is nonlinear because memory is nonlinear, and so is political revenge.

⭐ The Past → Shapes the Future

Oppenheimer’s political engagements from the 1930s come back to destroy him in the 1950s.

⭐ The Future → Rewrites the Past

Strauss’s hearings reinterpret earlier events, reframing Oppenheimer’s legacy.

⭐ Memory → Collides with Documentation

Oppenheimer’s emotional recollection vs. Strauss’s bureaucratic records.

⭐ Truth → Emerges from Contradiction

The dual structure lets the audience see the difference between:

- what happened

- what was remembered

- what was recorded

- what was weaponized

This makes the film less a biography and more a trial of memory itself.

🟥 6. The Trinity Test as the Narrative Fulcrum (The Point of No Return)

Trinity is the emotional center of the film.

It sits firmly in the fission timeline, because:

- the colors intensify

- the soundscape distorts

- the subjective psychological experience overwhelms

- the world feels fragmented

- time stretches unnaturally

The Trinity sequence is Oppenheimer’s moment of irreversible creation.

And from this point on:

FISSION timeline → becomes guilt-driven

FUSION timeline → becomes politically predatory

The test splits the timelines emotionally — another echo of atomic fission.

🟥 7. Oppenheimer vs Strauss: Thematic Counterpoints

⭐ Oppenheimer = The man crushed by his creation

Motifs:

- guilt

- moral uncertainty

- intellectual burden

- political naivety

- emotional fragmentation

⭐ Strauss = The man obsessed with reputation

Motifs:

- vanity

- insecurity

- political manipulation

- personal revenge

- bureaucratic power

Their timelines mirror and counterbalance each other.

They are the film’s dual protagonists — each representing a side of American power:

- creative power (Oppenheimer)

- institutional power (Strauss)

🟥 8. The Final Scene: Fusion and Fission Converge

The ending merges the timelines into a single philosophical conclusion.

Oppenheimer imagines a future where:

- chain reactions

- political escalations

- nuclear proliferation

- scientific breakthroughs

- geopolitical tensions

create a global fusion event — total annihilation.

Strauss’s version of history collapses.

Oppenheimer’s internal fears become the universal truth.

This is the ultimate narrative “fusion”:

Personal guilt + political consequence = existential reality.

🟥 Conclusion: Nolan Built a Story Where Structure Is the Message

The dual timeline structure of Oppenheimer isn’t a gimmick.

It is the film’s core meaning.

- Fission timeline → the birth of destructive power

- Fusion timeline → the consolidation of that power into politics

One is emotional.

One is institutional.

One is subjective.

One is historical.

One fractures.

One combines.

One creates.

One judges.

Together, they form a complete portrait:

The invention of the atomic age and the destruction of the man who made it possible.

This is not a movie about a man — it is a movie about how nations use men, discard them, and rewrite their legacy.

Nolan’s structure is the bomb.

And we are watching it detonate in slow motion